I don’t watch the Academy Awards. In a town built on cowardice and complicity in the face of fascism and entertainment as distraction over art as liberation, Hollywood and its institutions are ill-equipped to judge, let alone honor the best art produced in a year. So, I didn’t tune in to watch the two best singers in the joint with the most challenging performances of the year in a very radical film open up the awards show and bring the house down only to later lose awards to less challenging performances in offensive and exploitative films. I just caught the clips on Threads later.

But what I did see again this year—as every year—is a constant yearning for the validation of institutions that were created explicitly to keep us out. Social media was abuzz with praise for the Academy awarding “the first Black man” costume designer, the “first Dominican,” “the first Palestinian film,” in the Academy’s 97-year history, as if these are not embarrassing, damning indictments of this institution’s white supremacy and cultural irrelevance.

There were also cries about the lack of political speeches from the Oscars pulpit in an era of fascism and repression. Folks were big mad that Zoe “I did blackface and wore a prosthetic nose to play Nina Simone” Saldaña didn’t acknowledge the trans community or our government’s violent transphobia in her acceptance speech…for a movie that is undeniably transphobic and racist garbage. Others were upset about the visually stunning Dune: Part Two not getting its due when it’s literally the story of an Arab liberation group fighting a bunch of white colonizers for their lives, liberty, resources and land. Not quite this crowd’s cuppa tea! Though none of the Dune 2 cast or crew ever spoke up for Palestine as they appropriated Muslim fashion on the red carpet for their press tour, at least The Brutalist star Guy Pearce wore a Free Palestine pin on the red carpet last night. But I’m much more interested in the protestors who gathered outside the Dolby Theater in Hollywood to disrupt traffic and the red carpet with chants of “While you’re watching bombs are dropping” and “No celebration until liberation.”

The message was further elevated from the main stage when No Other Land, the Palestinian film about the zionist state’s illegal and brutal occupation of Palestine, managed to win Best Documentary in a room full of seething zionists. Its director Basel Adra used his acceptance speech to call on the world to “stop the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.” But the insult to injury was swift when the film’s Israeli co-director both-sided the genocide, centered himself, and “intertwined” Palestinian suffering under settler colonialism with his own suffering as a… *checks notes* …settler colonialist.

Without a doubt, in Zionist Hollywood, No Other Land could not have won as a purely Palestinian film by Palestinian filmmakers about Palestinians surviving oppression. They must be dignified and validated by a liberal zionist co-signer who will come behind a Palestinian and undermine his speech about liberation from zionist occupation and oppression by papering over it with the equivalent of a “coexist” bumper sticker.

And that’s just what made it into the ceremony.

As I mentioned last year, Marianne Jean-Baptiste in Hard Truths and Clarence Maclin in Sing Sing gave two of the best performances of the year and would never be recognized by the Academy for those performances. MJB played with care what this industry dismissed as an “angry Black woman,” but who was actually deep in suffering and depression, relentless and hilarious, harrowing and heartbreaking. Black women don’t win Oscars for roles that don’t service a white supremacist understanding of Blackness. We barely win them at all.

And Sing, Sing—a film about incarcerated men at the infamous prison finding hope and healing through a dramatic arts program—was 2024’s best film, not just thematically and cinematically. Still, it would never have a chance. This is not just because of the subject matter and the fact that white Academy voters refuse to watch themselves being racist on screen anymore (the “woke” days are over, hunny.) But also because of the radical way the film was made.

The film’s star, Colman Domingo, was paid the exact same amount for his work on the film as the film’s most entry-level worker, a production assistant. Each person who worked on the film also received an investment stake in the film so that the film’s financial success would be split amongst its workers based on the amount of work they did for the film. Workers owning the means of production? Not in Hollywood. The institution not only has every reason to dismiss the great art and message of this film, it also has every motivation to prevent its mass success. What if others see the model and *gasp* start to emulate it? This is a town built on hierarchy. The Academy is the zenith of elitism. Who would it serve to remind people that our power collectively surpasses the power of their institutions?

In 2023, after Beyoncé lost Album of the Year at the Grammys for the best work of her career, Renaissance, and several Black directors and Black women’s performances were ignored at the Oscars, I wrote a piece on “The Grammys, The Oscars, and the Prison of the White Imagination.” Despite Beyoncé winning her long-coveted Album of the Year Grammy this year for an album I’ll never listen to twice, the ideas I shared on these entertainment institutions and their purposes still stand, as well as our need as artists to tear them all down. Here’s an excerpt:

“We know that radical queer AF Black art like Bey’s “Renaissance” album is not going to be rewarded by anti-Black, white supremacist institutions, right? We know, but we still show up to the tweet party, we still turn on the TV with our fingers crossed, hoping against hope — only to be reminded of what we already know.

Take some time, lick your wounds, but please, my people, stand up.

Every year, these white supremacist institutions do the exact same thing, sprinkling a few wins for colored folks here and there to make believe that the door to the ultimate white validation prizes is still open. And every year, Black artists pour their hearts into their art, breaking records and literally creating the culture that makes every industry move, only for the door to be slammed in their faces.

It’s been 65 Grammys ceremonies, 95 Oscars ceremonies; what is it going to take?

And I’m not asking white people how much harder we need to tap dance for their love. The point of white supremacy, after all, is to be and remain supreme. There is nothing we can do but be beneath them, living or dead, as far as white supremacy is concerned. So, I’m asking us, my people, what is it going to take for us to get off their self-defeating, goal-post-moving hamster wheel of white supremacy?

Step one is acceptance, and that’s always the hardest. Wouldn’t it be easier if white people just stopped being racist? If they uprooted the systems of power that keep them in control of resources to the detriment of every other group of people that isn’t white? Sure. But at what point in history have they ever just stopped of their own accord?

There was an entire war fought over slavery, so, they didn’t freely stop back then. For about six months in 2020, white people and their institutions pretended that the cold-blooded murder of George Floyd by police was enough to change entire systems, to uproot the historic rot of anti-Black racism that had been their playground for actual centuries. But I’ll remind you, it wasn’t the snuff video of his brutal murder that brought about even the pretense of change; it was the masses who took to the streets around the world and the protestors who burned the Minneapolis Police 3rd Precinct headquarters to the ground in the name of Floyd that incited governments and corporations to act.

Now the backlash to even the tiniest movement of the needle has been so swift that our society has literally regressed in all areas, as white people have put their New York Times best-selling anti-racism books back on the shelf, never to be seen again. Ron DeRacist has made it actually against the law in Florida to teach white people their own abhorrent history. We’re back to denying that white supremacy and anti-Black racism are systemic systems of belief that control entire industries around the world. So no, my people, they are not going to just stop — not on the big stuff, like the system of policing or education, and not on the more subtle stuff, like the systems of creating and validating the images and sounds that shape our daily lives.

Your album won’t make them do it. Your movie won’t. Your talent won’t. You may wind up being in the handful of Black people who won a big one, who made history as a “first,” who gets invited into all of the rooms, who gets a seat at their table. But these industries only work by continuing the illusion that anyone can succeed in them if they work hard enough. Any success you get within their industries will not only be used against you when you hit the Black ceiling, but also against every other Black person who never even makes it through the door. No amount of Black success within their institutions will ever uproot the anti-Black reasons for which these institutions were created in the first place.

They were created to hoard wealth. They were created to seize power. They were created to quash organizing and rebellion of the working class.

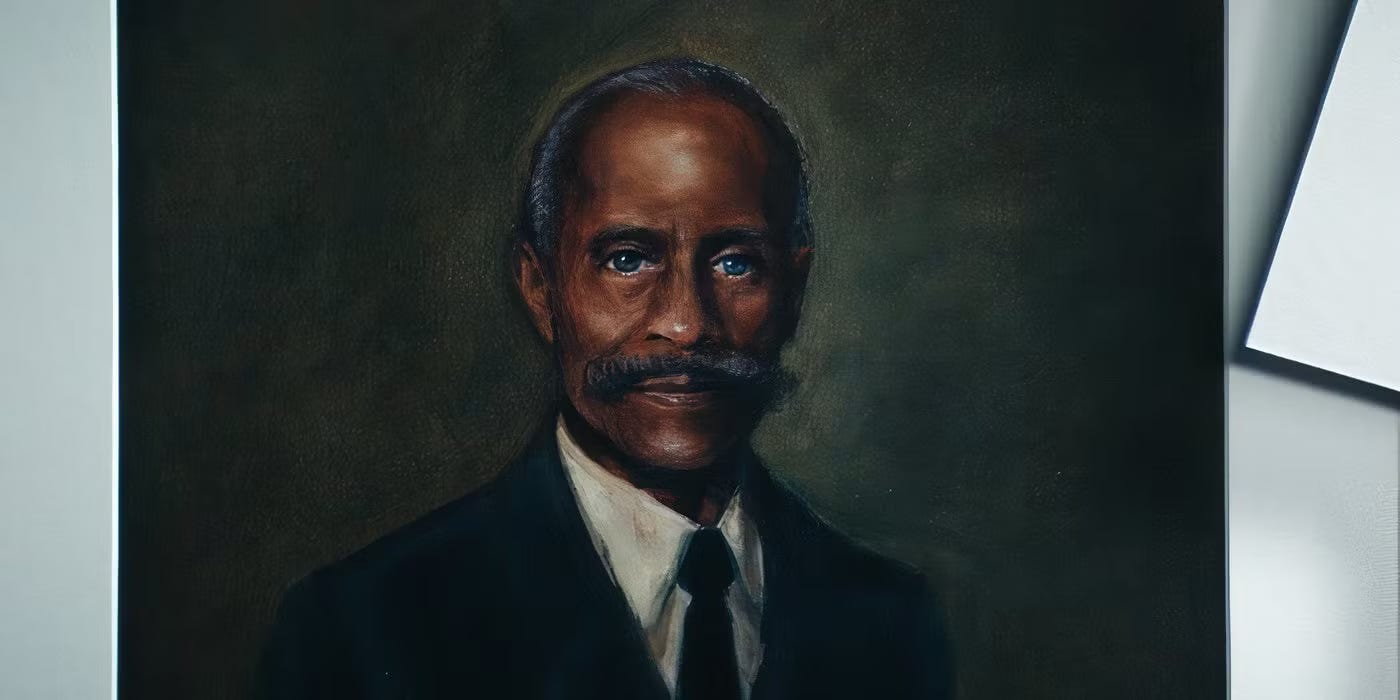

As the evil Oscars architect himself, Louis B. Mayer, once said, “I found that the best way to handle [moviemakers] was to hang medals all over them. If I got them cups and awards, they’d kill themselves to produce what I wanted. That’s why the Academy Award was created.”

The Grammys were literally created by white record executives who were upset about the impact of rock and roll on popular music and culture, with the goal of controlling the standard for what “quality” music is.

This is what the white imagination does; it stifles everything around it, keeping us in a loop of bland mediocrity, as they sit as judge and jury over the “quality” of our inherent right to create. The architects could not have been more explicit in sharing their nefarious purpose. Subsequent generations could not be more explicit in their intent to enact their nefarious plans in perpetuity.

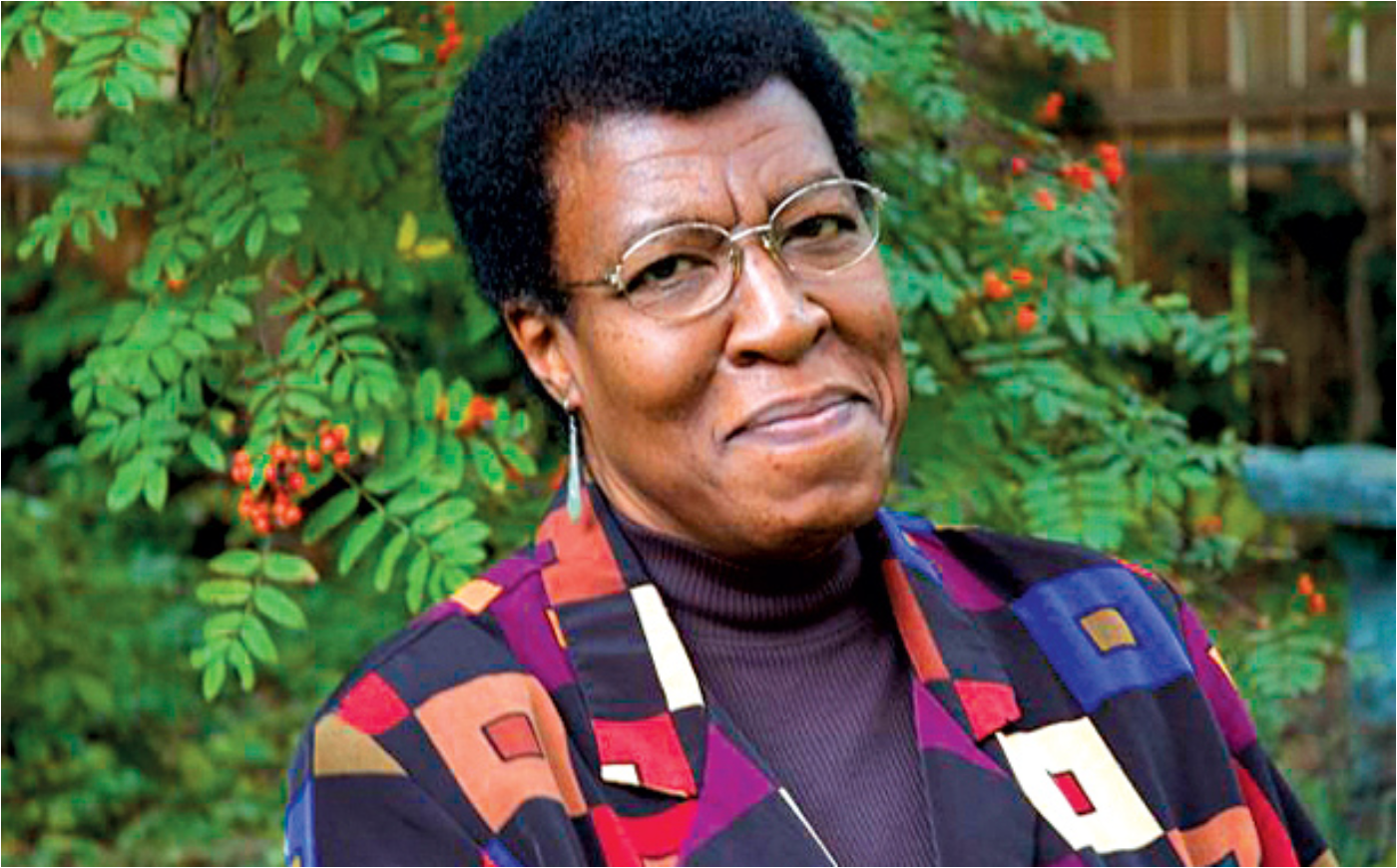

Mother Toni Morrison once said, “the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. … None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.”

We’ve tried begging. We’ve tried shaming. We’ve tried being more excellent than the white imagination can ever hold. But there will always be one more thing. The white imagination is a prison. It’s past time for us to tear it all down.

Their awards shows would crumble without Black talent in the audience, on the stage and in the virtual audience making them relevant. Let them crumble. But we cannot stop there.

In its place, we must not build the same institutions with the same white supremacist values, as we’ve seen time and again Black institutions upholding colorism, transphobia, queerphobia, ableism, capitalist exploitation and misogynoir, like good foot soldiers for white supremacy. Instead, we must get liberated from the white imagination that says we can’t be as boundless as we were created to be.

In the world that we artists create, there will be no anger and heartbreak over white supremacist snubs because the art we create was never for them and their rubrics and their judgment in the first place. We must reimagine ourselves as artists unchained by the desire for their distraction trophies.

We need the radical imaginations of the artists to create outside of these systems of oppression. If they’ve created systems to squash collective power, then we already know what we must do. We must organize the financing for our art. We must organize its production. We must organize our own distribution. Let’s pour our collective power into this work, into building the artists’ world, where we are free to work and create in safe environments for livable wages.

When we march and tear down and rebuild, let it not be for the goal of a VIP suite in their prison or a cell with a view; let it be for our total liberation from the limits of what they’ve said is possible.”

Turn the TV off on the Oscars and Grammys; stop submitting to them and lending them your credibility, culture and influence, and watch their power whither on the vine as we build another possible world together.

Stay watchin’,

Brooke